Amidst the vast landscapes of Australia, a struggle against water injustice echoes through the ancient grounds of indigenous communities. Farmers in New South Wales continue their defiance against the law by exceeding their allowed limit of water withdrawn by the equivalent of 16 000 Olympic swimming pools. How has water, a life-sustaining force, become a battleground for the indigenous Australians? Why does the Murray-Darling entitlement spark both hope and controversy?

Meric Sentuna Kalaycioglu

28 March 2024

In the heart of Australia, where the red earth stretches as far as the eye can see, indigenous communities are waging a battle for water justice in Australia’s largest river network, the Murray-Darling Basin. Spanning an area as big as France and Spain combined, the Basin stretches across parts of Queensland, New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Victoria and South Australia. Over 2.4 million people live within the Basin and it is home to more than fifty ethnic groups who lived in Australia prior to British colonization (known as First Nations), namely the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

While indigenous communities constitute 9.3% of the area’s population, they own just 0.2% of available surface water across the entire Basin. Known also as the heart of the country’s agricultural industry, the Basin grows 40% of the country’s produce, and is worth more than 22 billion Australian dollars each year.

Caring for Country: A Stewardship Born from Tradition

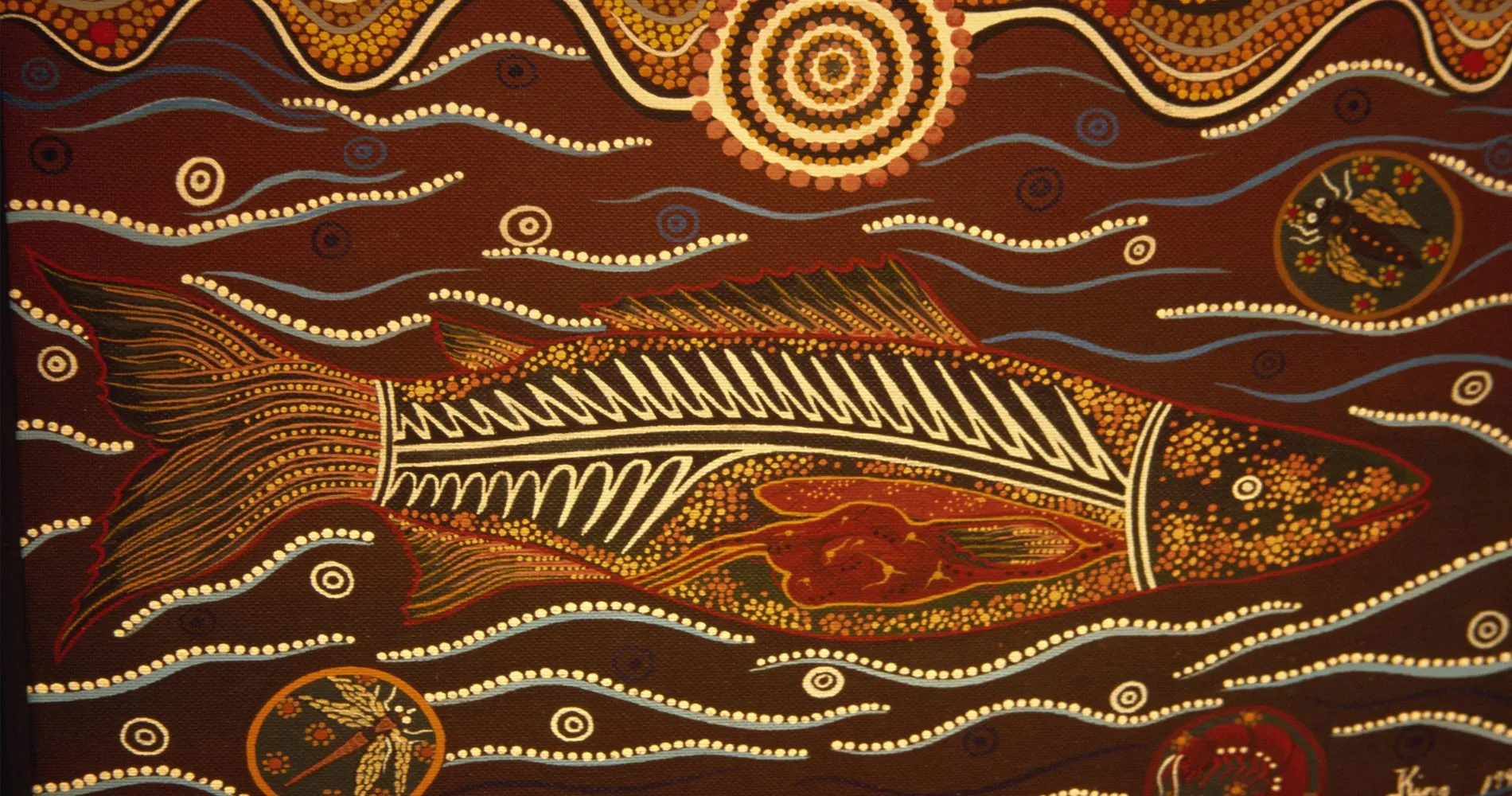

Water is more than a physical necessity for indigenous Australians; it is a spiritual essence woven into the fabric of their cultures, serving as conduits to connect with ancestral spirits, and shaping their ceremonies and rituals. The philosophy of “caring for country” guides indigenous Australians in their relationship with the land. This is a set of traditions deriving from the Aboriginal idea of preserving ecological balance and upholding cultural responsibilities, emphasizing that if you look after Country, Country will look after you. Water plays a pivotal role in this stewardship, sustaining totemic species and nurturing essential plants and foods.

Recent Government water management initiatives have disrupted this sacred connection, leaving indigenous communities grappling with the impact on their cultural practices and beliefs. The government-introduced water management arrangements, characterized by regulations, are challenging age-old practices, forcing indigenous communities to navigate a delicate balance between cultural heritage and modern water management systems.

Reflections on a decade of Basin-planning

In 2012, the Federal Government endorsed the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, a 13-billion Australian-Dollar initiative restricting the extraction of water from the Basin for purposes such as irrigation, drinking, industry, and aiming to rectify historical issues of over-extraction that have significantly harmed the rivers.

However, the Plan overlooked indigenous rights to own, manage and control water in the Basin. Subsequently, in 2018, the Australian Government committed 40 million Australian dollars to the Aboriginal Water Entitlements Program (AWEP), aiming to support the First Nations communities in the Murray-Darling Basin in acquiring cultural and economic water entitlements, along with associated planning activities. Despite this commitment, the Government failed to deliver on it due to several challenges. Over a four-year period, delays in AWEP implementation have arisen due to changes in government administrative arrangements, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the need to ensure appropriate delivery arrangements.

Administrative shifts between agencies, including the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR), the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE), the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA), and the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment, and Water (DCCEEW) since 2018, have added further complexity. Moreover, the diversity of First Nations cultures and identities in the Basin have complicated building a consensus on securing water entitlements.

The overall impact of not acting on the investment of 40 million Australian dollars appeared to be twofold. Firstly, it has hindered the intended support for First Nations communities in acquiring cultural and economic water entitlements, creating frustration and disappointment. Secondly, the delayed implementation and decreased value of the funding have compromised the effectiveness of the program, making it increasingly challenging for communities to engage meaningfully in the water market and fulfill their cultural and economic aspirations.

The DCCEEW which is responsible for the delivery of AWEP has emphasized the urgency of prompt action to avoid further delays in achieving beneficial outcomes for First Nations communities. Furthermore, common principles, such as enduring shared benefits, self-determination, and desire to maximize the impact of this huge contribution for water entitlements, have garnered agreement, with a focus on preventing this money being absorbed by administrative or incidental costs.

Consequently, more than a decade after the initial Plan, a further 9 million Australian dollars were pledged in April 2023 followed by the “Restoring Our Rivers” law in November 2023, under which AWEP’s funding was boosted to 100 million Australian dollars to advance First Nations’ water rights.

Hope for the rivers and the indigenous communities

In accordance with the 2012 Basin Plan, around 3000 gigalitres of water annually were to be reclaimed, primarily from farmers growing irrigated crops, and redirected to environmental purposes. Each year farmers receive allocated water quotas, and have the option to utilize or sell them. To reduce the river system’s water usage, the Government engaged in water entitlement buy-backs from farmers.

The “Restoring Our Rivers” law extends the Basin Plan’s original delivery timeframe by three years (to 2027), removes a previous water buy-back cap, allowing the Government to purchase more water for the environment and offers irrigators the option to lease, rather than sell, their water entitlements.

However, opponents argue that the expanded buyback approach may lead to adverse effects on various fronts, including impact on production, community confidence in the government, and decline in population due to migration to the urban centers, changing the dynamics of rural communities. Farmers continue their defiance against the buy-backs claiming it will reduce the value of agriculture in Australia by an estimated 855 million Australian dollars each year, increase food prices, shutdown farms and cost jobs. Because of these concerns, Environment Minister Tanya Pilbersek has expressed reservations about a complete buyback and is exploring alternative measures, such as efficiency projects.

Additionally, advocacy efforts led by groups like Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations (MLDRIN) ensured the inclusion of reforms supporting First Nations issues in the final legislation. The increased funding for the AWEP within this legislation enables First Nations in the Basin to purchase water entitlements for self-determined use, attempting to compensate for the unfulfilled 2018 funding commitment.

Bridging Perspectives for Water Justice

As the struggle for water justice unfolds, the challenge lies in finding a path forward that honors both the rights of indigenous Australians and the pragmatic water management demands of farmers. Under the new Restoring Our Rivers law, the AWEP has already started to evolve, respecting indigenous Australians’ spiritual and cultural connections to water. This marks a significant achievement in influencing the future of water management and the conservation of age-old traditions on this expansive territory.