Can an image of your face offer doctors an insight into your body’s apparent age and longer-term health prospects? A group of AI researchers from the Mass General Brigham Medical Center in Boston, USA believes it can. Your face might not just reflect who you are — it might help determine how well, and how long, you live.

Bruce McMichael

22 September 2025

A novel AI system “FaceAge” is making waves in the world of medical research. Developed using advanced deep learning techniques, FaceAge can estimate a person’s biological age simply by analysing a selfie photograph of their face. Researchers at Mass General Brigham Medical Center in Boston, where the app was created, believe this could identify significant health risks, predict life expectancy, and diagnose and inform treatment decisions for age-related diseases, including certain cancers.

There is a subtle difference between chronological age, which counts the number of years since birth, and biological age. Biological age reflects how a particular human body performs and is influenced by genetics, lifestyle, environment, and disease. For example, a 50-year-old who exercises regularly, eats well, and has no chronic conditions might present with a biological age of someone ten years younger.

Conversely, another 50-year-old with obesity, diabetes, and high stress levels could appear biologically closer to 60. Understanding these differences can be crucial in determining personalised healthcare strategies, such as managing aggressive treatments like radiotherapy.

A statement from Mass General Brigham researchers found that “patients with cancer, on average, had a higher FaceAge than those without and appeared about five years older than their chronological age. Older FaceAge predictions were associated with worse overall survival outcomes across multiple cancer types. They also found that FaceAge outperformed clinicians in predicting short-term life expectancies of patients receiving palliative radiotherapy”.

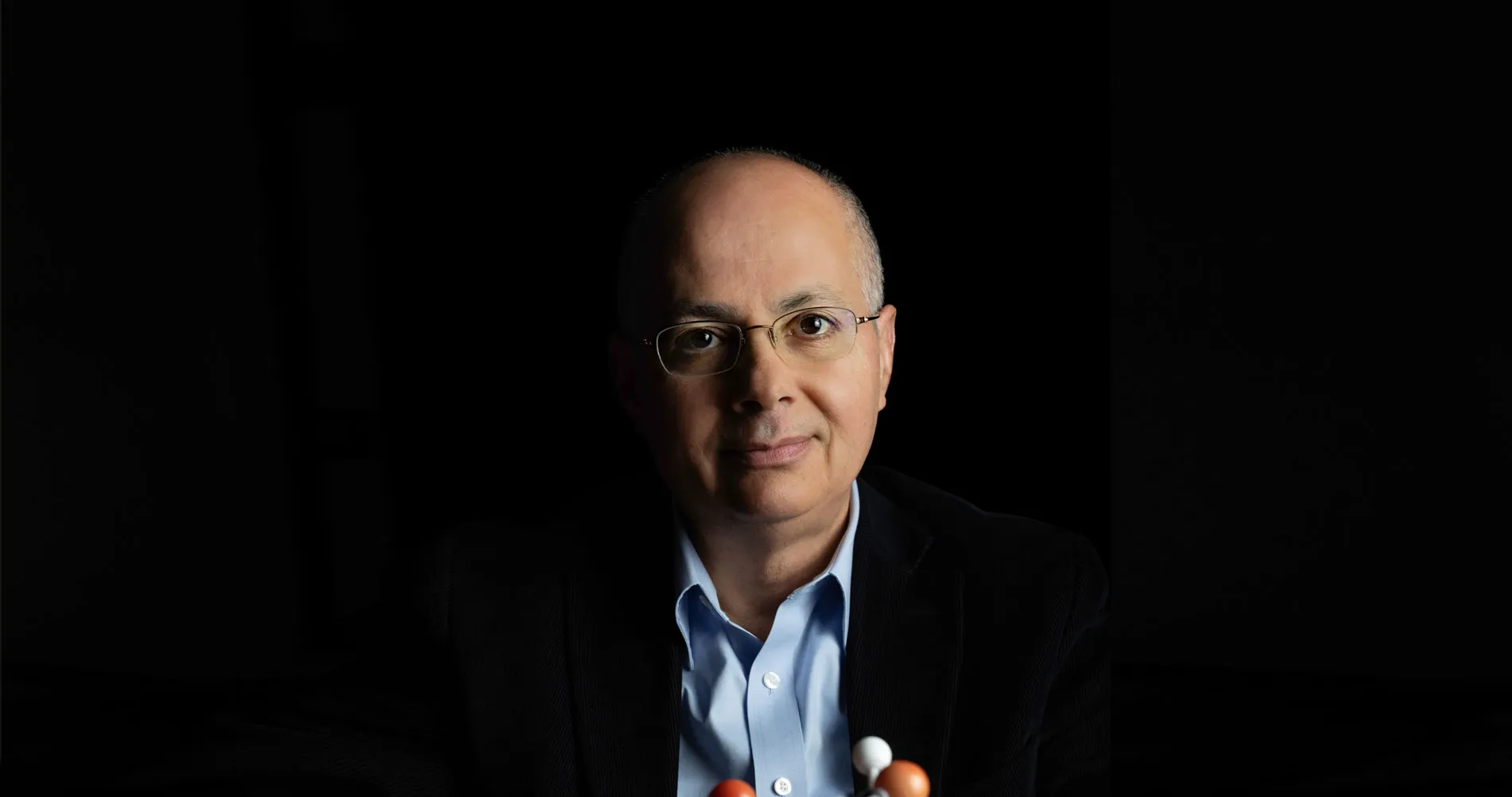

According to Hugo Aerts, director of the Mass General Brigham Artificial Intelligence Medicine (AIM) programme: “We can use artificial intelligence (AI) to estimate a person’s biological age from face pictures, and our study shows that information can be clinically meaningful. This work demonstrates that a photo, like a simple selfie, contains important information that could help to inform clinical decision-making and care plans for patients and clinicians. How old someone looks compared to their chronological age really matters — individuals with ‘face ages’ that are younger than their chronological ages do significantly better after cancer therapy.”

How FaceAge Works

Using over 50,000 photographs of presumed healthy individuals and over 6,000 images of cancer sufferers, an algorithm was created and tested. Using this dataset, Mass General Brigham researchers noted that “results showed that cancer patients appear significantly older than those without cancer, and their FaceAge, on average, was about five years older than their chronological age. In the cancer patient cohort, older FaceAge was associated with worse survival outcomes, especially in individuals who appeared older than 85, even after adjusting for chronological age, sex, and cancer type.”

Through this training, FaceAge learned to detect subtle patterns in facial features, such as skin texture, wrinkles, fat distribution, and even micro-expressions, that correlate with biological ageing processes.

What sets FaceAge apart from prior age-estimation systems is its clinical utility. Most face-age algorithms aim to estimate a person’s age, which is often used in entertainment apps or for digital content. But FaceAge is not guessing how old you appear to others; it’s estimating how old your body truly is on a cellular and systemic level, and what that means for our health.

Across peer-reviewed studies, FaceAge has been demonstrated to estimate biological age with high accuracy while predicting clinical outcomes, including mortality risk, more accurately than chronological age alone. This is a potential game-changer in areas like oncology, geriatrics, and public health.

FaceAge’s biological age estimates strongly correlated with patient outcomes, according to Mass General Brigham. Patients with a higher biological age than their chronological age often had significantly worse survival rates, even when other health metrics looked normal.

These results suggest that FaceAge may be capturing hidden health signals that are not obvious to the human eye or traditional diagnostic tools. For example, facial features may reflect the cumulative effects of inflammation, cellular senescence, and oxidative stress — factors strongly linked to ageing but often challenging to detect in general medical practice.

Researchers hope that by integrating FaceAge into medical workflows, healthcare providers will gain new insights into patient care and treatment. For example, oncologists might use it to personalise treatment intensity; geriatricians could monitor ageing trajectories over time; primary care doctors might be able to identify patients who seem healthy but their biological ageing is progressing, suggesting that they are ageing rapidly.

Ethical and practical implications

As with any AI system that interfaces with healthcare, FaceAge raises significant ethical concerns. Is it fair or advisable to base medical decisions on something as superficially simple as a face photo? What about privacy and consent, especially when facial recognition is already a hot-button issue in society?

Developers of FaceAge have tried to pre-empt these concerns. The model is not designed for surveillance or identification, and it anonymises and encrypts data to meet strict medical privacy standards (such as HIPAA compliance – Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act). Moreover, it’s intended to support human judgment, not replace it.

The science of ageing

FaceAge is part of a larger movement toward precision ageing — using biomarkers, machine learning, and big data to understand and intervene in the ageing process. What makes FaceAge interesting to developers is its non-invasive, low-cost, and easily scalable nature, and all it requires to work is the use of a graph. This makes it especially promising for use in low-resource settings, mobile health applications, and remote monitoring areas where traditional diagnostic tools may be impractical or too expensive.

In consumer health, people may eventually use apps powered by FaceAge-like algorithms to track the effectiveness of their lifestyle changes, much like how fitness trackers work today. Already, a handful of startups are exploring ways to offer “face ageing scores” to users interested in anti-ageing routines or longevity science.

There is also growing interest in using biological age as a health-span metric — a way to quantify how long someone can expect to live a healthy, independent life. Chronological age doesn’t tell you whether a 70-year-old is thriving or declining. FaceAge might.

The technology could extend into related sectors including wellness, insurance, and public health policy. Employers, or indeed insurance providers, could use biological age assessments to encourage healthy behaviour.