After decades of failing to address the lethal consquences of post-war nuclear waste, residents of the St Louis area of Missouri are finally seeing signs of culpability and justice, but is this enough to protect future generations?

David Deegan

9 January 2026

Coldwater Creek, a modest tributary in northern St. Louis County, Missouri, has been at the center of long-standing concerns over radioactive-waste contamination from uranium processing of the early US nuclear weapons programme.

Beginning in the 1940s, under the top-secret wartime Manhattan Project, Mallinckrodt Chemical Works in downtown St. Louis processed uranium, producing up to a ton of uranium every day, thereby generating substantial amounts of radioactive waste.

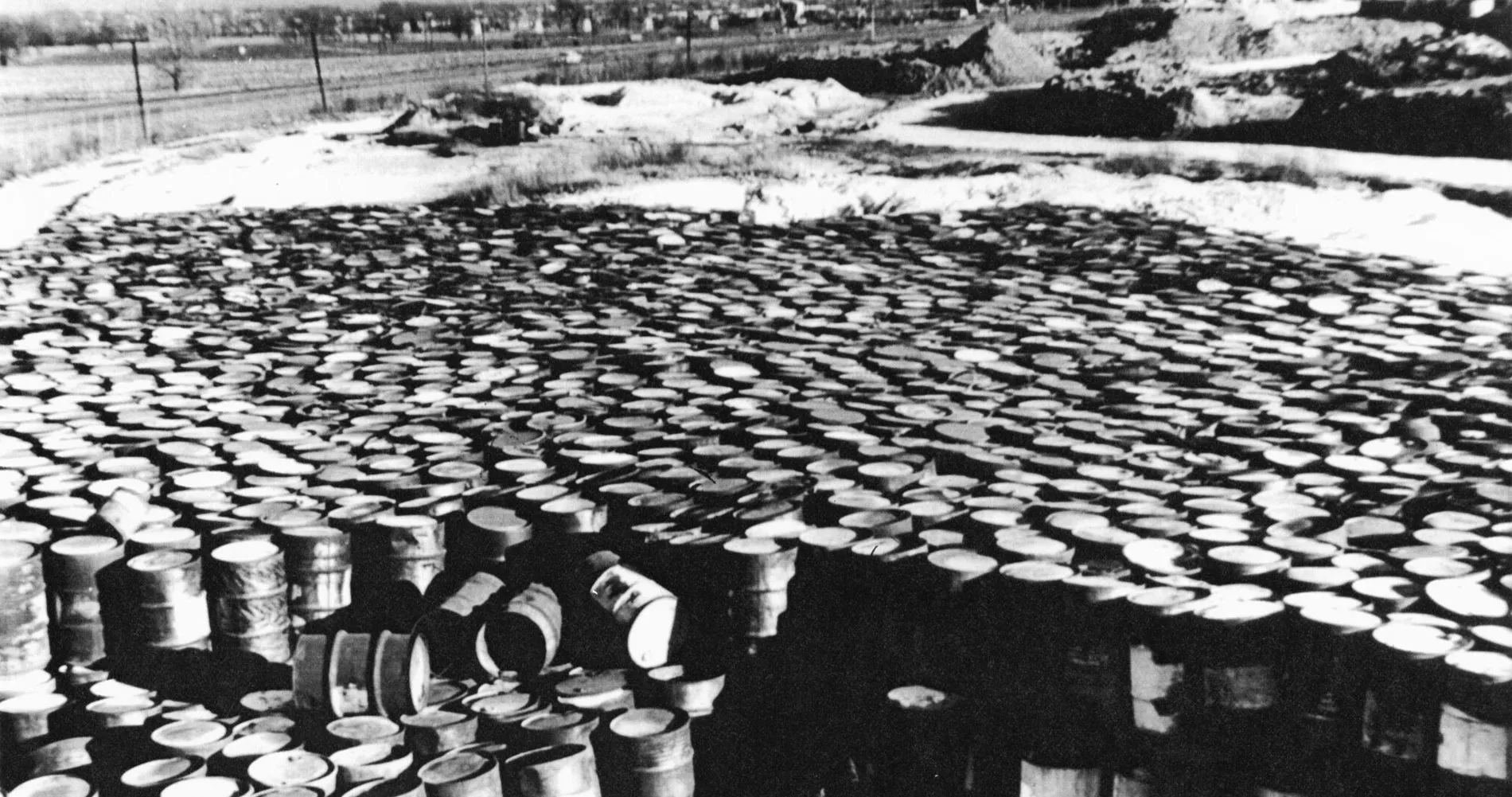

After WWII, some of this waste was stored near what became the airport-storage site adjacent to Coldwater Creek, Missouri. Over time, portions of the waste were sold to private firms for reprocessing; one such firm, the Cotter Corporation, moved materials to a site on Latty Avenue, again near Coldwater Creek. Over time, deteriorating containers and environmental exposure allowed radioactive residues to leach into the surrounding environment. Waste that could not be reprocessed was eventually disposed of at the West Lake Landfill, Missouri in the 1970s.

The contamination was not broadly acknowledged until 1989, when the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) formally classified the storage site and surrounding Coldwater Creek flood plain as hazardous, triggering cleanup under the federal Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (FUSRAP).

By then, over 60 000 people had lived, built homes and raised families within one mile of the creek, many unaware that their homes, backyards or playgrounds might lie atop or beside contamination. Residents have described patterns of cancer and other serious illnesses in their neighborhoods. Linda Morice, longtime resident and author of “Nuked”, an account of the long-term effects of radiological exposure in St. Louis, recalled that after both her parents and brother eventually died of lymphoma, a relative warned her: “Everyone on this street has a tumor.”

Since 1997, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has overseen cleanup under FUSRAP. But the complexity of remediation, including scattered contamination in residential areas, public land and floodplains has made progress slow and difficult. Early estimates projected a relatively brief remediation period (around 8 years), but as of the latest publicly available planning, the Corps now estimates that cleanup will continue until approximately 2038.

Meanwhile, many individuals and families affected by illnesses they believe stem from radiation exposure have struggled for decades to obtain recognition or compensation. Litigation efforts often failed because of challenges in proving a direct causal link between exposure and disease, particularly given the long latency of radiation-linked illnesses.

On July 27, 2023, the U.S. Senate considered an amendment sponsored by Senator Josh Hawley as part of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) that would extend the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) to cover people harmed by improperly stored nuclear waste, including in the St. Louis area. Because the House initially failed to pass the amendment, Hawley and allies reintroduced a standalone RECA bill on January 24, 2025, co-sponsored by Senators from other affected states.

On 12 June 2025, Hawley announced that a significantly expanded version of RECA had been included in the base text of the so-called “Big, Beautiful Bill”, a major US legislation regarding the budget and reconciliation package. In his public statement, he framed the expansion as a long-overdue act of justice for Americans whose health suffered because of federal nuclear-waste mismanagement.

Under the expanded RECA provisions, residents of impacted areas in Missouri, including those near Coldwater Creek and the West Lake Landfill, become eligible for compensation for radiation-linked illnesses. The expanded law also extends coverage for uranium miners, “downwind” populations from nuclear testing and survivors in other states, potentially opening the door for thousands of new claims from residents who previously lacked access to federal support.

Under the new law, eligible survivors may receive payments and support without having to prove individual causation, a significant departure from past litigation standards. They must only show that they or a relative had a qualifying disease after working or living in certain locations during specific time frames.

For many residents, Hawley’s bill represents the first robust federal acknowledgment of the risks posed by decades-old contamination. The expanded RECA offers a clearer path to compensation for people who lived, worked or attended school near the creek, often for years before illnesses appeared.

Announcing the RECA expansion at a public rally in July 2025, Hawley framed the legislation as an effort to “deliver justice and overdue compensation” for those whose health was harmed by government negligence. He stated: “RECA is the government saying, ‘what we did was wrong. Lying to you was wrong, and we are finally going to make it right.’”

At the same time, clean-up remains a separate and ongoing challenge. While compensation addresses health and economic harms, environmental remediation, including soil removal, sediment decontamination and long-term monitoring, still proceeds on a protracted timeline under federal oversight.

The legacy of Coldwater Creek’s radioactive contamination looms large, a result of wartime uranium processing, post-war disposal practices, and decades of inadequate environmental oversight. For decades, affected residents sought recognition, cleanup, and compensation; their efforts often met resistance or legal setbacks.

With the 2025 expansion of RECA, many of those residents now have a clearer, federally-sanctioned pathway to compensation for radiation-linked illnesses. This marks a major policy shift: from decades of neglect and obfuscated responsibility to a public and political acknowledgment of the damage and the need for remediation and support.

Yet the environmental legacy remains; full cleanup of Coldwater Creek and the wider St. Louis-area contamination continues to be a slow, complex process. The expanded compensation is a critical step towards justice for affected individuals. But as long as contaminated soil, sediment, and water persist, the risk to future generations remains.