This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Austrian Karl von Frisch’s 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology for his ground breaking discoveries on bees. Frisch showed that bees exhibit complex behaviors and social learning which are critical for their ability to collect nectar and thrive. Their nectar-gathering simultaneously pollinates human food crops. As the global human population continues to grow and food supplies become ever more critical, polluting activities are causing bee populations to decline. Research has shown that the complexity of their social learning means that swift reversal is imperative.

David Deegan, 10 April 2023

German version | Spanish version

Bees, along with other insects, collect nectar from flowers to make honey, which they use to feed their young, and as reserves during the winter months. They are social insects, dependent for their survival on the large colonies in which they live.

A honeybee scouting for flowers will initially rely on both vision and scent, but flowers fade quickly, so to ensure sufficient honey for the colony, other bees must be swiftly directed to the same source. When scout bees return to the hive and meet others, they will perform intricate dances with their tails and abdomens, known as a waggle-dance. This behavior had been noted as early as the 4th century BC by Aristotle, but this dance was first scientifically investigated by the Austrian zoologist Karl von Frisch, who share the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology with Austrian Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen from the Netherlands for discoveries on bees, including the dance of the bees. Bees use behavior patterns to convey information on food sources and other critical information to other bees.

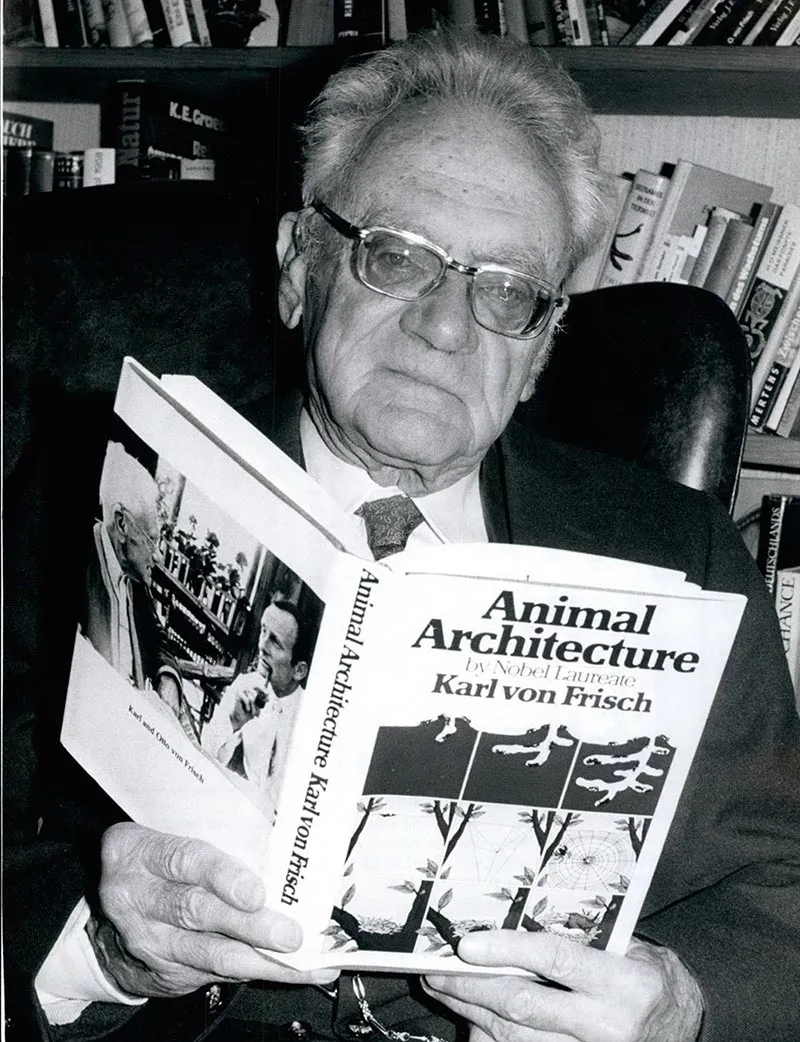

90th Birthday of Karl Ritter von Frisch.

On November 20th 1976, Karl Ritter von Frisch, professor for zoology and comparative anatomy, will become 90 years old. The famous scientist, who was born in Vienna and now lives in Munich, proved that fishes can distinguish colors and that bees orient themselves by the polarized skylight. Karl Ritter von Frisch studied in Vienna and Munich and lectured in Rostock from 1921, from 1925 in Munich and from 1932 in Breslau. From 1946 in Graz and from 1950 to 1958 again in Munich at the Institute for Zoology. He wrote eight books about biology (his latest called Animal Architecture, 1974, was translated into English, French and Italian).

He received 30 international awards, is six time an honorary doctor of several universities and was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1973 for his research about the language of bees.

© IMAGO / ZUMA/Keystone

Current research tracks bee movements by means of tiny radio transmitters fitted to individual bees, but in the 1920s when he began his research, Karl von Frisch had to rely on tiny dabs of paint he placed on the bees’ abdomens. This ingenious but labor-intensive marking system enabled him to track individual bees within a swarm and to determine the meaning and purpose of the dances.

He discovered that when dancing in the hive the scout bee will posture at a particular angle, and this corresponds to the angle to the sun that the bee flew on its path to the nectar-laden flowers. The speed at which it waggles its abdomen indicates the distance of the food source from the hive. The waggle-dance of the honeybee is believed to be one of the most complex behaviors in the animal world, and its decoding by Karl von Frisch earned him the Nobel Prize.

Karl von Frisch’s unique expertise on bees and their role in food production was especially important during the 1940s when a plague decimated European bee populations.

Further research has shown that bees will dance to communicate other situations. In 2018 a Japanese research team showed that bees perform a waggle-dance to warn the colony of predatory wasps. The dance informed the colony of an imminent attack, and the bees then collected strong-smelling plant materials and smeared them at the hive entrance to deter the wasps.

Bees are synonymous with honey, but we depend on them for so much more. As they collect nectar, the flower’s pollen coats their bodies and the bees carry that while pollen to other plants. The transfer of pollen is essential for the ability of plants to produce–grain crops are primarily pollinated by the wind, fruits, nuts and vegetables are pollinated by animals, predominantly insects. And of those, bees are the largest group of pollinators. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that 70% of human food crops which supply 90% of the world’s nutrition are pollinated by bees. In Europe alone, 4000 vegetable varieties exist thanks to pollination by bees, which also boost crop yield. The value of one ton of a pollinator-dependent crop is approximately five times higher than a crop not dependent on bees.

A 2010 report by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) stated that since 1960, agricultural production that is not dependent on animal pollination had doubled, while agricultural production requiring animal pollination had increased four-fold. So global agriculture is becoming increasingly pollinator-dependent.

Scientists know that bees are dying for a variety of reasons—pesticides, drought, habitat destruction, nutrition deficit, air pollution, global warming and more.

Air pollution affects the chemicals that flowers produce to attract bees, which destroys scent trails. Scents that could travel over 800m in the 1800s can now reach less than about 200m from the plant, which decreases the ability of the crucial first scout bee to discover a new food source.

Various types of pesticides not only damage the health of bees but also affect their ability to find food. Pesticides have been shown to kill their brain cells, especially those responsible for processing visual stimuli. Bees affected by pesticides stagger like drunkards, thereby affecting their ability to dance and communicate the location of food to other bees.

In 2023 a research team from the UK and China demonstrated that bumblebees were able to communicate techniques for solving non-natural challenges. Bumblebees who had learned how to open plastic puzzle-boxes containing sugary liquid were able to demonstrate this technique to other bees. Some bees who had not been privy to a demonstration spontaneously opened the puzzle-boxes but were significantly less proficient than those that learned in the presence of a demonstrator bee, suggesting that social learning was crucial.

A study published on 9 March 2023 showed that young bees actually learn from older scouts. A research team from China and the USA created colonies in which all honeybees were the same age. The young bees could not learn from any experienced dancers because there were none in the group studied. When the bees found food, they would perform a waggle-dance for others in the hive, but the dance was based on their instincts and incorrectly indicated both the direction and the distance to the food source. Over time, they learned and improved the waggle-dance, perhaps by observing bees from other natural colonies, but they were never able to indicate the exact distance to food. The researchers posited that not only do bees learn to communicate distance by observing the waggle-dance of older and more experienced scouts, but they do so very early in their lives and may not be able to improve later in life.

The China/US team’s recent discovery that “you cannot teach an old bee new tricks” demonstrates that artificial re-creation of bee populations may never be completely successful. Therefore, unless action is taken to boost the health of bee populations, global food shortages may soon become a widespread reality.