As Trump’s Congo peace accord faces its October test, a troubling question emerges; can you broker lasting peace when the primary combatants aren’t at the table and mineral rights matter more than the million displaced Congolese caught in crossfire?

Michael Asiedu

15 October 2025

As Congo and Rwanda prepare to implement security measures this October under a Trump-brokered peace deal, the world is witnessing what may be the most transactional approach to conflict resolution in recent memory. The Washington Accord, signed on 27 June 2025, establishes a framework where Rwanda agrees to withdraw its troops from Congolese territory while Congo commits to neutralizing the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), Hutu militants who fled to Congo after the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Joint monitoring mechanisms are to oversee implementation, with operations set to begin in October.

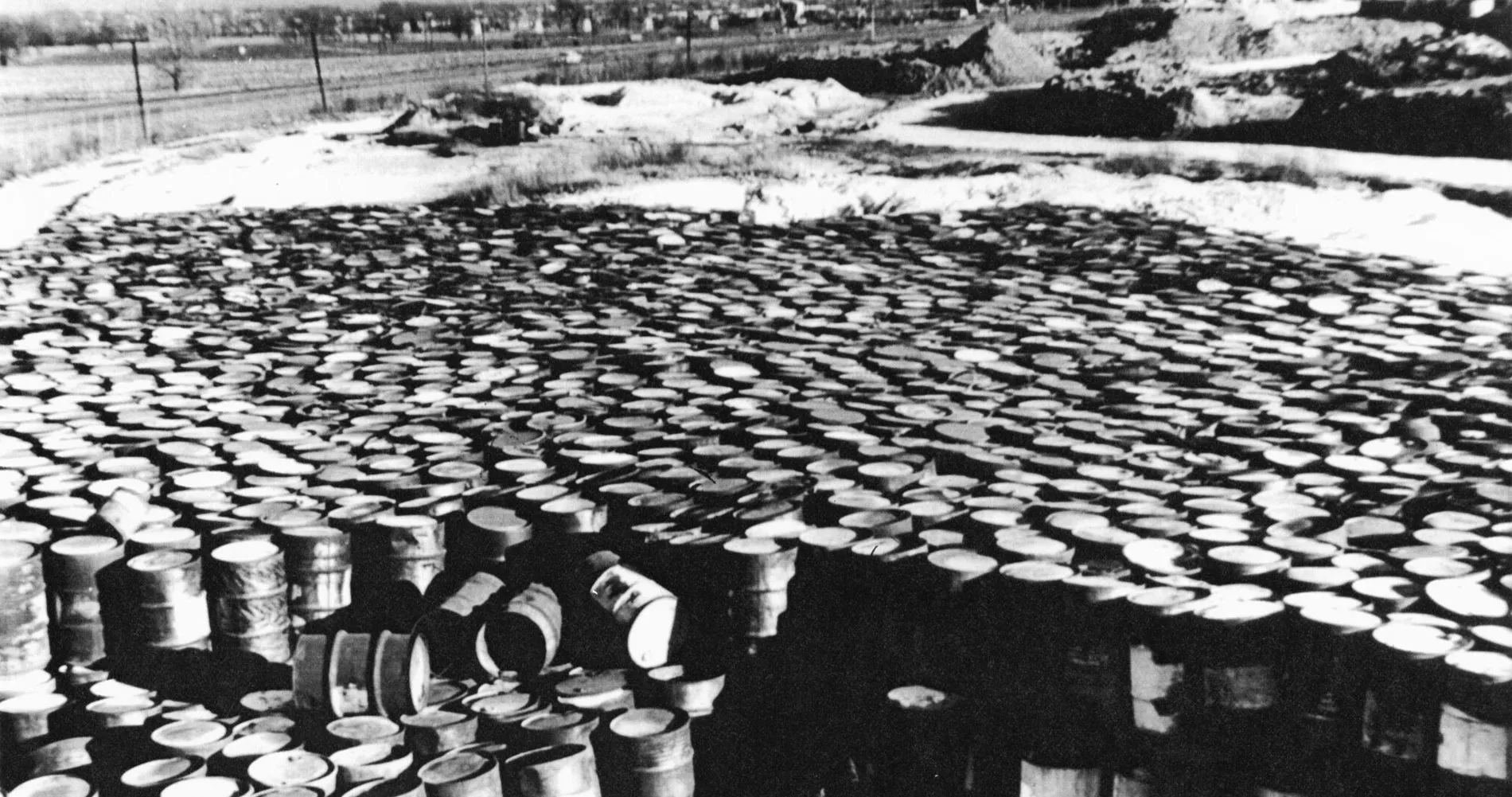

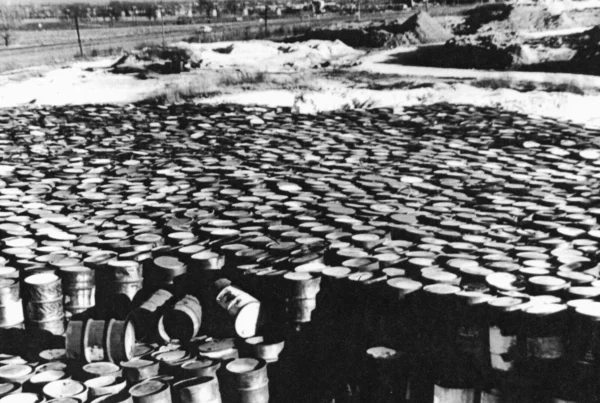

But the fine print reveals a troubling reality. This isn’t primarily about ending suffering in eastern Congo, it’s about securing America’s access to critical minerals. In exchange for brokering the deal, the United States receives access to mineral extraction rights in Congo’s resource-rich eastern provinces, home to cobalt, tantalum, copper, and lithium deposits critical to modern technology.

When President Trump announced the signing, he was remarkably candid, “We’re getting, for the United States, a lot of the mineral rights from the Congo as part of it.” Rarely has the exchange been stated so boldly; peace for cobalt, security for coltan.

The timing of October’s implementation deadline offers the first concrete test of whether this deal represents genuine progress or merely another chapter in three decades of failed peace efforts. Operations to eliminate the FDLR threat and facilitate Rwandan troop withdrawal are set to begin between October 21-31, with completion expected by year’s end. Yet significant obstacles suggest this timeline is dangerously optimistic.

The most glaring flaw is the absence of M23 rebels from the agreement. M23, the March 23 Movement, a Tutsi-led rebel group that has been fighting in eastern Congo since 2012, is the primary armed force on the ground, yet it is not party to this peace deal. In January 2025, M23 launched a devastating offensive, capturing Goma, a city of two million, and later Bukavu, marking the largest escalation since 2012. The rebel group has explicitly stated, “This deal does not concern M23.” But how can a peace agreement succeed when the primary belligerent isn’t party to it? Separate Qatar-led negotiations with M23 have already missed their August deadline, and the group’s leaders have declared their intention to march on Kinshasa.

The fundamental disagreements that have plagued previous peace efforts remain unresolved. September meetings in Washington were “repeatedly bogged down in disputes over the nature of M23 and Rwanda’s relationship to it.” Rwanda continues denying its support for M23, despite substantial evidence. UN reports document 3000 to 4000 Rwandan troops on the ground, and investigators have concluded that Kigali exercises command and control over the rebels. This is not mere assistance, it is active military involvement dressed up as plausible deniability.

Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi has declared that “the withdrawal of Rwandan troops from Congo and the end of Rwandan support for M23 were non-negotiable conditions for genuine peace.” Yet the Washington Accord carefully avoids explicitly addressing M23’s territorial gains, instead calling for Rwanda to end “defensive measures”, a euphemism that allows both sides to interpret success differently.

The humanitarian toll of this diplomatic maneuvering is staggering. The UN and Congolese government estimate between 900-2000 deaths just from the January 2025 Goma offensive, with hundreds of thousands displaced. UN documentation shows over 319 civilians killed by M23 between 9-21 July 2025. Farmers camping in their fields during planting season, women and children caught in crossfire, and entire communities forced to flee repeatedly. These are the people for whom peace cannot come soon enough, yet they are conspicuously absent from the negotiating tables in Washington and Doha.

Perhaps most revealing is the Trump administration’s broader approach to the region. Earlier this year, a single social media post from Trump threatened to close USAID operations, putting half a million eastern Congolese at risk and cutting off their primary humanitarian lifeline. Now, the same administration claims credit for delivering peace. The message is clear, America’s interest in the Congo extends only as far as its mineral wealth, not the welfare of its people.

Michael Odhiambo, a peace expert working in eastern DRC, captures the local sentiment, “Many ordinary citizens are hardly moved by the deal and many will wait to see if there are any positives to come out of it.” He notes fears that “American peace may be enforced violently as we have seen in Iran,” with anxiety that future violence “could be justified by America protecting its business interests.”

This skepticism is well-founded. Previous ceasefires and accords have often collapsed. The region has seen countless peace agreements since the aftermath of the 1994 Rwandan genocide sent perpetrators fleeing into eastern Congo, triggering decades of proxy wars, resource exploitation, and humanitarian catastrophe. Each time, external actors promising their agreement will be different. Each time, the fundamental drivers of conflict remain unaddressed, competition for resources; ethnic tensions; and regional power dynamics.

The October implementation will reveal whether this deal has any substance beyond photo opportunities and mineral concessions. Will Rwandan troops actually withdraw, or will they simply rebrand their presence? Will the FDLR genuinely be neutralized, or will it remain a convenient justification for continued intervention? Will joint monitoring mechanisms have real authority, or serve as diplomatic window dressing?

What’s certain is that lasting peace in eastern Congo requires more than great power bargains over mineral rights. It demands genuine reconciliation, addressing legitimate grievances on all sides, disarming and integrating armed groups, establishing accountable governance, and crucially centering the voices and needs of Congolese communities who have borne the conflict’s heaviest burden.

As October approaches, the world should watch carefully. Not just whether troops withdraw, or ceasefires hold, but whether this deal serves the Congolese people or merely facilitates the extraction of their resources under the guise of peace. History suggests the latter.