For decades, the open ocean was treated as a dumping ground for radioactive waste. Far below the surface of the northeast Atlantic – where scientists once assumed inert and lifeless ecosystems – hundreds of thousands of (formally) sealed containers filled with nuclear waste were discarded. Today, their precise locations are uncertain, their condition largely unknown, and their ecological consequences only partially understood. A French-led scientific expedition set out to confront this legacy.

Lukas Barcherini Peter

11 February 2026

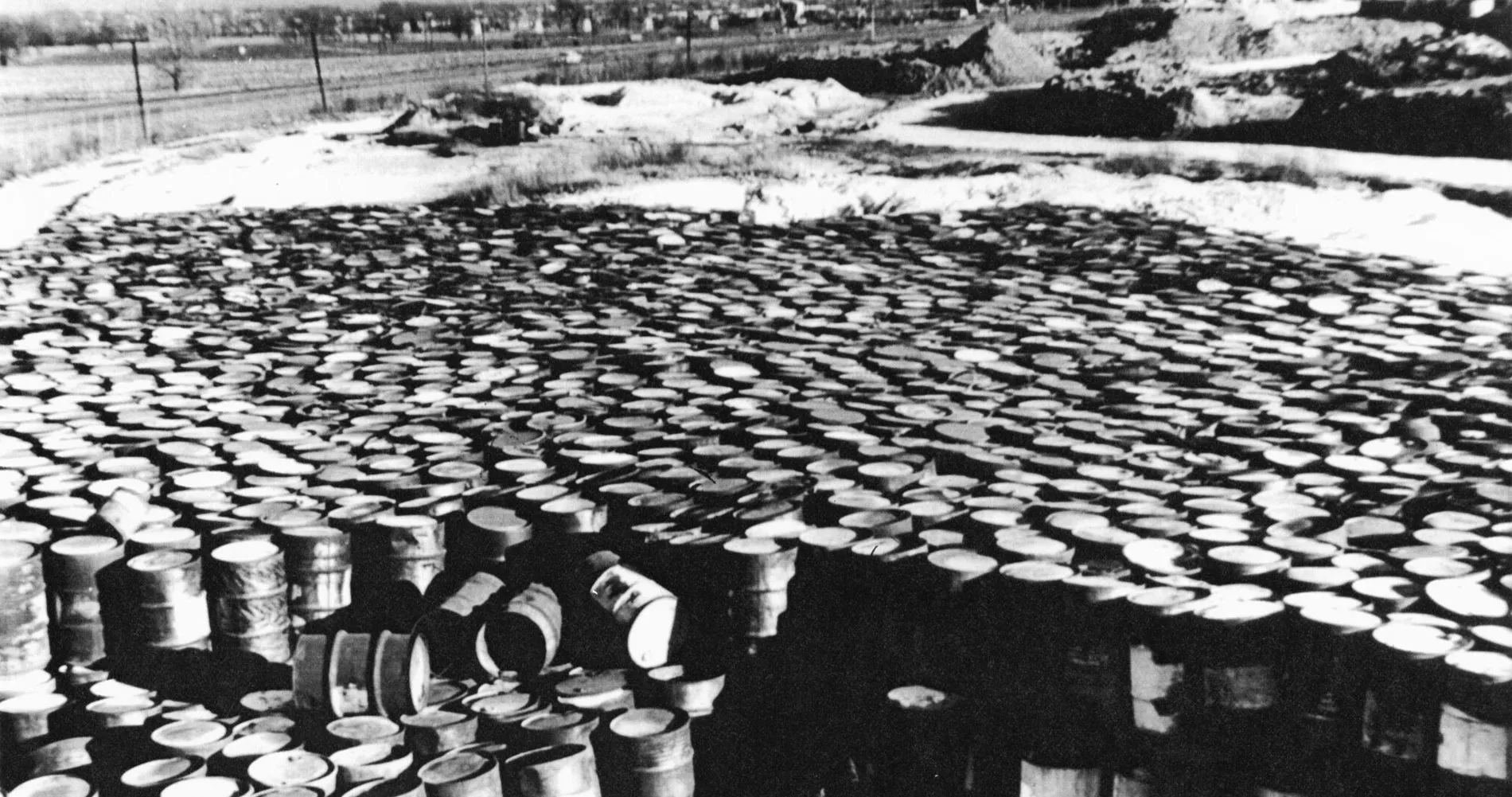

Between 1946 and 1993, disposing of radioactive materials at sea was widely considered acceptable. Waste was immobilised in asphalt or concrete, sealed inside metal drums hoped to be watertight, and released into international waters. While becoming public only in 1980, the practice was deemed as practical, safe, and economical. At least 14 European nations carried out nuclear dumping operations at more than 80 marine sites across the Atlantic. The northeast Atlantic alone holds the densest concentration, with an estimated 200 000 barrels resting on the seabed at depths of up to 4000 meters.

Formally ending the practice took decades. While dumping began in 1946, meaningful regulation only emerged in 1975 with the London Convention, the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter. Disposal of highly radioactive waste was banned that year, but a comprehensive prohibition was not agreed upon until 1993.

According to a 1999 IAEA Waste Disposal Inventory, roughly 53.4 percent of the dumped material was classified as low-level waste, of which more than 93 percent was disposed of at northeast Atlantic sites, primarily by European states. Another 43.3 percent consisted of more hazardous material, including entire reactors and spent nuclear fuel, dumped by the former USSR.

Detailed maps of dumping zones were seldomly documented, and records vary widely between countries. Previous monitoring campaigns were further constrained by limited technology, often relying on blind sampling without precise knowledge of where barrels lay. Over past decades, currents, sediment movement, and corrosion have also shifted the containers, making direct assessment of their integrity difficult, one of the central motivations behind the French mission.

Researchers from France’s CNRS, (French National Centre for Scientific Research) the ocean science institute Ifremer, and the French oceanographic fleet are now attempting to close that gap with the NODSSUM mission. The multidisciplinary team includes nuclear physicists, geologists, oceanographers, biologists, and marine chemists. Central to the effort is UlyX, an autonomous underwater vehicle capable of descending to 6000 metres.

Equipped with sonar, UlyX can scan wide areas of seabed for anomalies consistent with waste containers. Once detected, it can hover above the barrels to capture high-resolution images, allowing scientists to assess their distribution and condition. A second phase, planned for 2026, will focus on detecting radionuclides in seawater, sediments, and marine life, while establishing background radiation levels to distinguish contamination from other nuclear sources.

Evidence of barrel degradation is not new. In 2000, Greenpeace documented corroded and collapsing containers at the Casquets trench in the English Channel. The footage revealed advanced structural failure and raised concerns about leakage into surrounding waters.

Even at the time of disposal, it was understood that the barrels would not remain intact indefinitely. Radioactive waste was therefore not placed loosely inside the drums, but embedded in bitumen or asphalt, forming a solid mass encased within a steel shell. The corrosive effect of saltwater on steel had, of course, long been known. The limited lifespan of the containers was thus an accepted constraint, not an unforeseen failure.

Cost considerations were explicit. A confidential meeting record of the German federal government dated 11 May 1962 states: “The costs [of disposal] are drastically reduced by final disposal through dumping at sea, (particularly through the use of the cheapest possible containers) […].” Germany also played an active role in promoting international marine disposal, as confirmed by internal 1962 memoranda of the Federal Ministry for Research.

Crucially, far less attention was paid to the long-term interaction between bitumen and biological processes once the steel drum had degraded. Early assumptions portrayed the deep seabed as cold, inert, and largely lifeless. These assumptions have since been overturned. Deep-sea research has shown that abyssal environments (the deep ocean floor) host active microbial communities.

Over long timescales, this degradation may weaken the protective matrix surrounding the waste. The critical question, therefore, is whether the steel and bitumen barriers degrade faster than the radioactive material itself decays into less harmful forms. While much of the waste dumped in the Atlantic is classified as low- or intermediate-level, this distinction can be misleading. Radionuclides decay at vastly different rates: some diminish within decades, while others persist for billions of years.

Plutonium isotopes have also been detected in deep-sea organisms from the North Atlantic abyssal plains, raising concerns that bioaccumulation could transport 238Pu through the food web. Although concentrations are generally low and often dominated by naturally occurring radionuclides such as polonium-210 and potassium-40 (see: F. Carvalho et al., 2011), a link to dumped material has not been conclusively ruled out. Addressing this unresolved uncertainty is the central aim of the current French mission, which combines visual identification of containers with targeted sampling of water, sediments, and marine life, representing a methodological step-up in the investigation of this legacy.

Mission leaders stress that the goal is not to judge past decisions, but to document their consequences using modern tools. Only a small fraction of 3000 of the estimated 200 000 barrels can be examined during a single voyage, yet the mission establishes a new baseline: for the first time, uncertainty itself is being treated as a problem requiring systematic investigation rather than dismissal.

The current first phase of the mission merely scanned the seabed for the barrels. It will take additional time before the first radiological and technical results can be published. Yet regardless of the measured level of contamination, the former practice itself stands as a stark warning. This is precisely why the precautionary principle exists. It is meant to prevent irreversible actions when long-term consequences are uncertain; and uncertain they unquestionably were. While dumping once was a cheap and convenient method for disposing of man-made waste, it now seems all too familiar that the true burden and costs of a method were simply pushed forward and handed to future generations. Any potential recovery, if it proves feasible at all, will almost certainly come at costs orders of magnitude higher than the short-term savings claimed at the time, paired with a threat that can, in principle, compromise human physical integrity.