On the 19th of December 1972, Apollo 17 returned back to Earth, ending the moon-program. With six landings completed, the United States had proven its technological superiority over the USSR. The space race seemed over, budgets were cut, and for fifty years the Moon fell silent. That silence is now ending. China, Russia, and the US are engaged in a new lunar contest. This time, the race is not merely to reach the Moon first, but to remain there. At its center stands an old idea reborn: harnessing nuclear power to keep humanity’s outpost alive through the long lunar night.

Lukas Barcherini Peter

11 December 2025

German version

A new space race is underway, this time focused on establishing the first permanent, nuclear-powered base on the Moon. The drive to be “first” mirrors the ambitions of the original space race. The1967 Outer Space Treaty between the US and the USSR prohibits any nation from claiming territory in space, yet it leaves room for de facto control. A lunar base could effectively create a “keep-out zone” under the guise of safety and non-interference, restricting access to nearby resources and asserting dominance without formal ownership.

The idea of building a nuclear reactor to power research and resource-harnessing on the Moon dates back to the late 1950s, when US and Soviet engineers first realized that solar power could never sustain a permanent outpost. A lunar day lasts roughly 28 Earth days – two weeks of sunlight followed by two weeks of freezing darkness. Daytime radiation pushes surface temperatures beyond 120 °C (250 °F), while the long night drops them to –129 °C (–200 °F). In theory, solar energy surpluses from the day could be stored to survive the night, but the extremes make this unfeasible.

The best batteries known today fail under these conditions. They degrade rapidly when charging under high heat and stop functioning altogether when frozen. A reactor, by contrast, operates independently of sunlight and temperature, producing both electricity and heat without interruption.

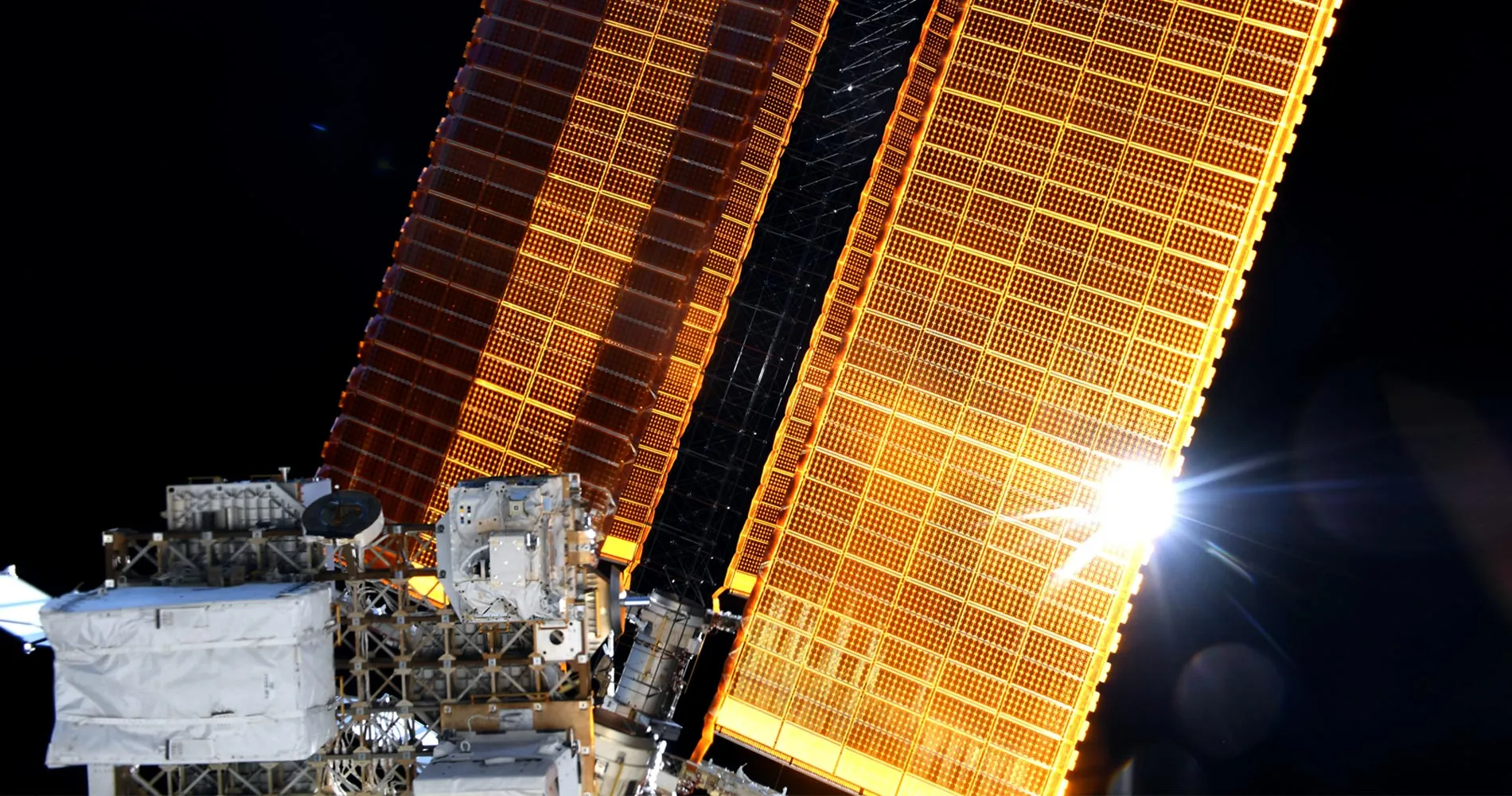

As part of the US Artemis program – announced in 2017 to return astronauts to the Moon – the US took its first step towards such a system in 2022. NASA awarded three contracts worth five million dollars each to design a compact fission reactor for the lunar surface. The initial concept envisioned a 40-kilowatt system capable of providing stable power for at least ten years.

In April 2025, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) announced that its upcoming International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) – a joint project with Russia and fifteen other states from the Global South, announced in 2021 – would include a nuclear power plant as part of the Chang’e-8 mission, targeting completion of the ILRS around 2035. The announcement shifted the pace of the entire field. Within a month, US Secretary of State Mr. Duffy confirmed that NASA’s program would be fast-tracked: its target power output raised from 40 to 100 kilowatts and its deployment schedule advanced to 2030.

At the proposed scale, both reactors are miniature marvels. A standard nuclear power plant on Earth produces about 1000–3000 megawatts; the proposed lunar systems would generate one to three million times less power, yet still enough to sustain a base. The challenge lies not in generating enough power but in delivering it. A 100-kilowatt reactor is expected to weigh around six tons – close to the limits of existing launch vehicles.

For the US, Blue Origin’s Blue Moon MK1 could deliver roughly half that mass per flight, requiring two launches. SpaceX’s Starship HLS could in theory carry the full payload, but only after a series of 8–12 refueling launches in Earth orbit. China’s Long March 10 is projected to transport between five and eight tons to the lunar surface, with two launches required for the reactor and its landing system.

Both sides aim to establish their bases near the Moon’s south pole. Unlike the equatorial plains where the Apollo and Soviet Luna missions landed, this region contains craters in permanent shadow that may hold vast reserves of frozen water. Over billions of years, comets and asteroids have deposited ice in these perpetually cold areas – unlike the equatorial ice, which long ago evaporated under sunlight. Access to this trapped water could be the decisive factor in transforming a temporary outpost into a sustainable lunar base.

This is where In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) becomes essential. Using the reactor’s electricity, water can be extracted, purified, and split into hydrogen and oxygen through electrolysis. Water and oxygen sustain life; hydrogen, when mixed with oxygen, forms rocket fuel. Beyond water, the Moon may also host strategically valuable resources such as helium-3 – a potential fuel for future nuclear fusion reactors on earth – along with rare earth elements, titanium, and aluminum-rich minerals that could be crucial for construction and energy production.

Which lunar base will be functional first remains uncertain. While China’s Chang’e program enjoys steady political backing, details about its joint plans with Russia are scarce, as little information is publicly disclosed. The Chang’e-7 mission, expected to deliver a lunar rover in August 2026, could pave the way for a future reactor setup. In the US, the picture is equally unclear: the administration plans to cut NASA’s 2026/2027 budget by roughly 24%, casting doubt on the mid-2027 launch of Artemis III, intended as the first crewed lunar landing since 1972. Furthermore, NASA has yet to decide between Blue Origin and SpaceX for its lander of the nuclear cargo, and both companies are reportedly facing technical setbacks.

Behind these engineering achievements lies a strategic and geopolitical dimension. US officials have warned that a Sino-Russian outpost could claim the “keep-out zone” around its infrastructure under the pretext of safety. Producing energy on the Moon is more than infrastructure – it is influence. The first permanent power source on the Moon will anchor not only scientific work but also political presence. Whichever nation establishes it first will shape the norms of lunar activity – from access to ice deposits to the boundaries of cooperation and competition.

For the nation that first successfully establishes a permanent presence on the moon, one thing is certain: this or the next generation of astronauts, cosmonauts, and taikonauts will establish humanity’s first extraterrestrial, self-sustaining outpost – a testament to how far our species has come. In the long run, the Moon’s abundant resources could prove vital not only for sustaining life and industry on its surface but for developing the technologies and experience needed to explore deeper into the Solar System.