Concerns about long-term health conditions are being raised around the use of a chemical flavouring used in e-cigarettes, commonly known as vapes. Fears about the catchily titled ‘Popcorn Lung’ disease revolve around a chemical additive known as diacetyl. The condition is also known as ‘food flavourer’s lung’ and is a descriptor for an inflammatory lung condition involving scarring and a narrowing of the breathing tubes, making breathing difficult.

Bruce McMichael

2 June 2025

Chinese version

The complex-sounding 2,3-butanedione (CH3CO)2, to give the chemical diacetyl its full name and chemical formula, is used by food manufacturers to provide certain products, such as popcorn, a specific flavour, in particular creamy, milky, buttery notes. And that’s where the popular name or this condition originates.

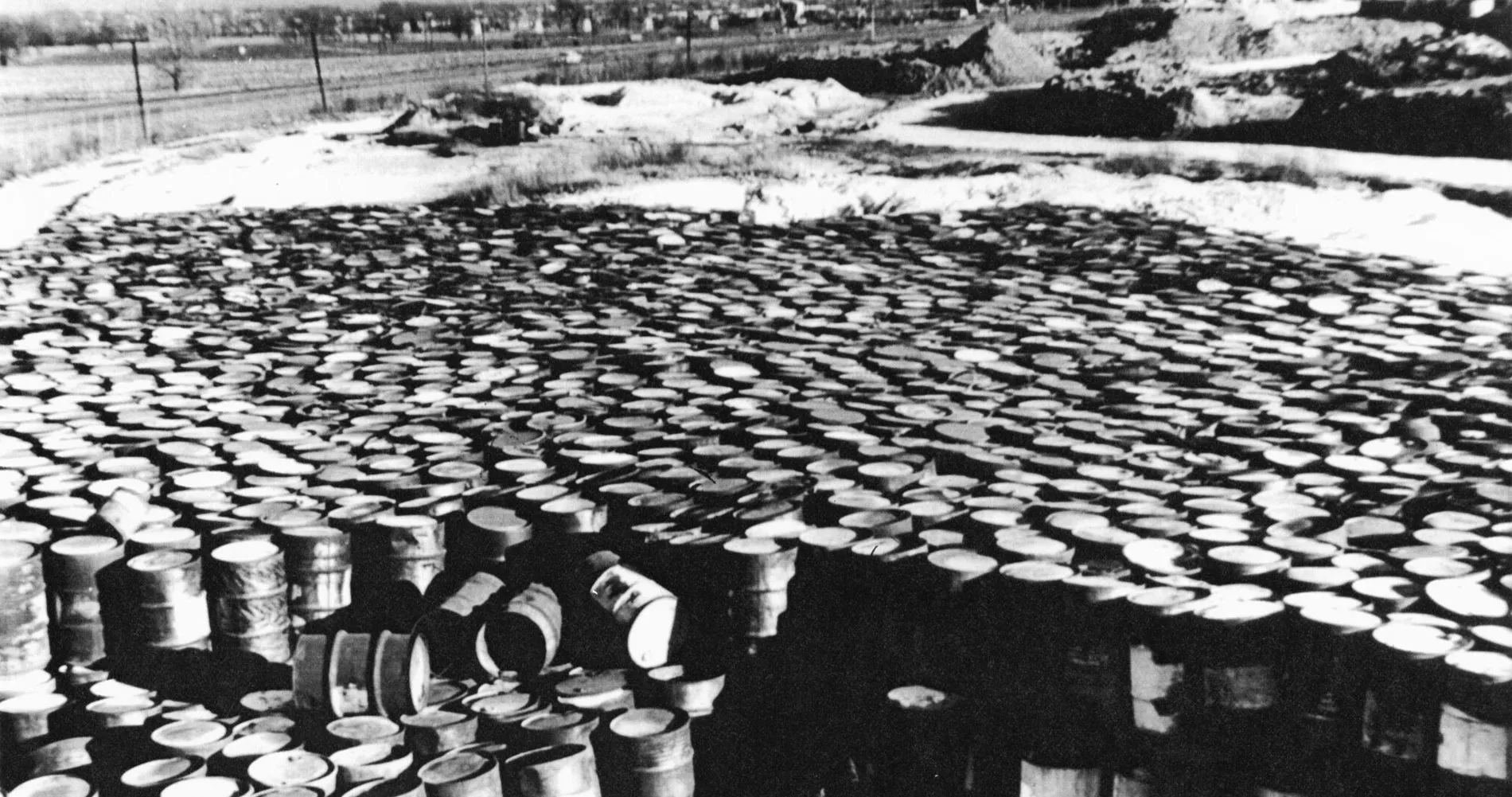

The use of flavourings in food products was reported in US newspapers in the early 2000s following reports of an epidemic of lung disease conditions amongst workers making microwavable popcorn. At the time, the flavouring chemicals were thought safe to use. However, this only applied when eaten, with no attention given to the impact should they be inhaled during production.

Breathing in diacetyl has been linked to popcorn lung, referred to in medical literature as bronchiolitis obliterans. This disease manifests as lung scarring and narrowing airways, similar to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cancer Research UK states that; “popcorn lung is an uncommon lung disease caused by scar tissue growth across the lungs, which blocks airflow. Popcorn lung isn’t cancer.”

While sufferers of popcorn lung can be treated, the condition cannot be cured. Treatments range from a course of steroids to the use of inhalers and, ultimately, a lung transplant. While this flavouring may be tasty, in the US, it has been linked to deaths and hundreds of cases of bronchiolitis obliterans.

Concerns were raised when diacetyl appeared in vape liquids, especially buttery, creamy, and sweet flavours. Although levels in vapes are lower than those inhaled by factory workers, the idea is that inhaling even small amounts daily could still pose a risk over time. There’s no known ‘safe’ level of inhaled diacetyl, and inhalation standards are stricter than food standards.

Even though many reputable vape juice makers have removed diacetyl, some flavoured e-liquids might still contain it — or similar chemicals such as acetyl propionyl, which can also be risky.

Inhaling diacetyl isn’t the same as eating it — our lungs are less robust than our digestive systems. Several major popcorn manufacturers removed diacetyl from their products. However, some people are still being exposed to diacetyl – not through food flavourings as a worksite hazard, but through e-cigarette vapour.

The disease has also been detected in workers employed at a coffee roasting plant and in certain cheeses such as Cheddar, but only in quantities as low as 0.05 m per 100 gm.

However, while diacetyl is used in certain foods, it has been banned in the UK as a flavouring in vapes and e-cigarettes. Diacetyl was similarly banned in e-cigarettes and e-liquids in the EU in 2016 under the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD). This ban also applies to the UK despite Brexit.

There is scant evidence for linking vaping and e-liquids to cases of popcorn lung. According to one online vape retailer, “This is because e-liquids and e-cigarettes produced in the UK and EU are required by law to conform to the TRPR and Tobacco Products Directive (TPD), which bans the use of diacetyl as an ingredient in any e-liquid or e-cigarette”.

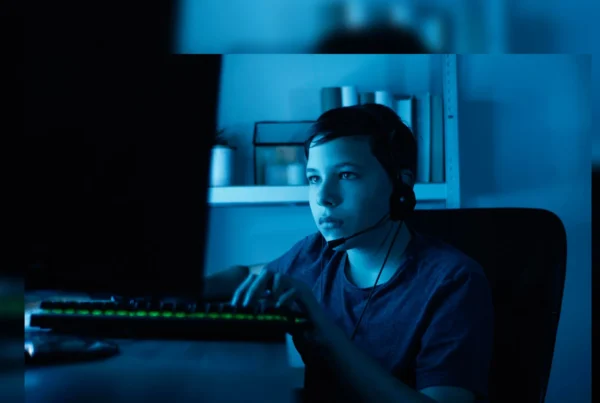

However, there is no control over the content of illegal vapes. For example, since early 2022, UK government officials have seized six million vaping products, many of which were to be sold to children under the age of 18, marketed with names to appeal to that demographic, such as Aspire, Lost Mary and Elfbar.

Research by BBC Health journalists in early 2023 found that vapes, mostly illegal, confiscated from school pupils in the West Midlands, England contain high levels of metals, such as chromium and lead. The BBC reported test results showed that those using these supplied “more than twice the daily safe amount of lead and nine times the safe amount of nickel”. World Health Organization research says that “high levels of lead exposure in children can affect the central nervous system and brain development.”

According to the respected US-based medical centre, the Cleveland Clinic, several other chemicals are similarly associated with popcorn lung, including ammonia, chlorine and formaldehyde.

Professor of respiratory medicine at the University of Birmingham, England, David Thickett, has previously warned about the long-term lung health of vaping. The direct delivery of high doses of nicotine to the lungs through vaping could also be more harmful than traditional tobacco-filled cigarettes, laboratory studies undertaken at the university showed.

Teens are also tempted to vape by the product’s sweet flavours, low costs and high nicotine content. Belgium’s health minister, Frank Vandenbroucke, says that one unintended consequence of marketing disposable e-cigarettes is that young people and new users who had not previously smoked are attracted to using vapes.

Disposable vapes are now banned in Belgium. This is part of the European Commission’s long-awaited proposal to achieve smoke- and aerosol-free environments, replacing the current recommendations since 2009 and is part of a longer-term scheme, the Beating Cancer Plan.

In Australia, vapes are only available from pharmacies, and in the UK, single-use vapes will be banned from mid-2025. Reusable vape sales are not affected, as some health officials believe that they can help some people quit smoking and hence reduce deaths from nicotine and, ultimately, lung cancer.

Given the established dangers of diacetyl exposure through inhalation, it is clear that limited reformulation of so-called e-juice and lack of sufficient legal oversight might well negatively impact consumer health.

So, while vaping may well be thought of as a safer alternative to smoking, exposure to chemicals such as diacetyl shines a spotlight on the need for greater transparency, stricter regulation, and continued research to understand the long-term health effects fully.