The European Union’s approach to international accountability reveals a stark and increasingly indefensible double standard. Brussels has moved swiftly and decisively against Russia—sanctioning Moscow, freezing state assets, and insisting that Russia must finance Ukraine’s reconstruction. Yet no comparable framework has been applied to Israel, despite the devastation of Gaza and mounting genocide allegations. This contradiction was highlighted by the case of Italian journalist Gabriele Nunziati, whose dismissal shows how even asking a politically inconvenient question can put press freedom under pressure in Europe’s own capital.

Silvia Caschera

19 January 2026

During a European Commission midday briefing on 13 October 2025 the Italian journalist Gabriele Nunziati, a contributor to the Rome-based news agency Agenzia Nova, posed a question that went to the heart of the matter. “You have repeatedly said that Russia should pay for the reconstruction of Ukraine. Do you think Israel should pay for the reconstruction of Gaza, given that it has destroyed almost the entire Strip and the civilian infrastructure?”.

On October 27, following a series of tense internal conversations in which Agenzia Nova questioned the appropriateness of Nunziati’s query, the organization stressed the negative reputational impact this question might have on its social media platform. In the agencies view, the situations of Russia and Israel were fundamentally different. Nunziati’s collaboration was terminated effective immediately. The agency described the question as “technically incorrect” and “out of place”.

The response from press unions and elected officials was immediate. The International and European Federations of Journalists demanded his reinstatement, while several Italian MEPs denounced the dismissal as an unacceptable restriction on press freedom. On 11 November 2025, the ECMPF (European Center for Press & Media Freedom) issues an open letter to the Editor-in-Chief of Agenzia Nova, Bormioli, (see also https://www.ecpmf.eu/open-letter-regarding-the-dismissal-of-journalist-gabriele-nunziati/). Their letter was signed by a number of organizations of the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR) and stated that “Journalists have both the right and the duty to ask questions, including critical or difficult ones, to ensure the democratic accountability of political decision-makers. Any attempt to silence such voices constitutes an unjustifiable form of censorship.”

In the aftermath, the European Commission itself publicly clarified that it had never contacted the news agency and reiterated that journalists are free to ask any question at its briefings. On 11 November 2025, the European Parliament submitted written questions for answer to the Commission regarding the safeguards established under the European Media Freedom Act, particularly Article 6, and whether the Commission’s actions which resulted in the dismissal of the Nunziati have implications for editorial independence and freedom of inquiry. (see also https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-10-2025-004453_EN.html)

The mere facts prove that the editorial decision by Agenzia Nova was incredibly biased towards Israel.

Against Russia, the EU has implemented some of the most far-reaching financial measures in its history. More than EUR 200 billion in Russian sovereign assets have been immobilised across European jurisdictions, with the profits channeled into assistance for Ukraine. The European Parliament has approved extraordinary lending mechanisms to support Ukraine, including a package of up to EUR 35 billion to be repaid from future proceeds generated by those frozen assets. In short, the EU has built a sophisticated legal and financial architecture whose explicit purpose is to ensure that Russia bears material responsibility for the consequences of its aggression.

No equivalent framework has been constructed in relation to Israel. Despite internal discussions throughout 2025 on the possible partial suspension of the EU–Israel Association Agreement, proposals to sanction extremist Israeli ministers, and debates about conditioning trade preferences, the cooperation partnership between the EU and Israel remains largely intact, pending unanimous decisions by member states. The only sanctions adopted so far under the EU’s Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime target individual parties; violent settlers in the West Bank and specific groups that obstruct humanitarian aid deliveries to Gaza. These measures, while symbolically significant, do not resemble a structural accountability mechanism aimed at the Israeli state.

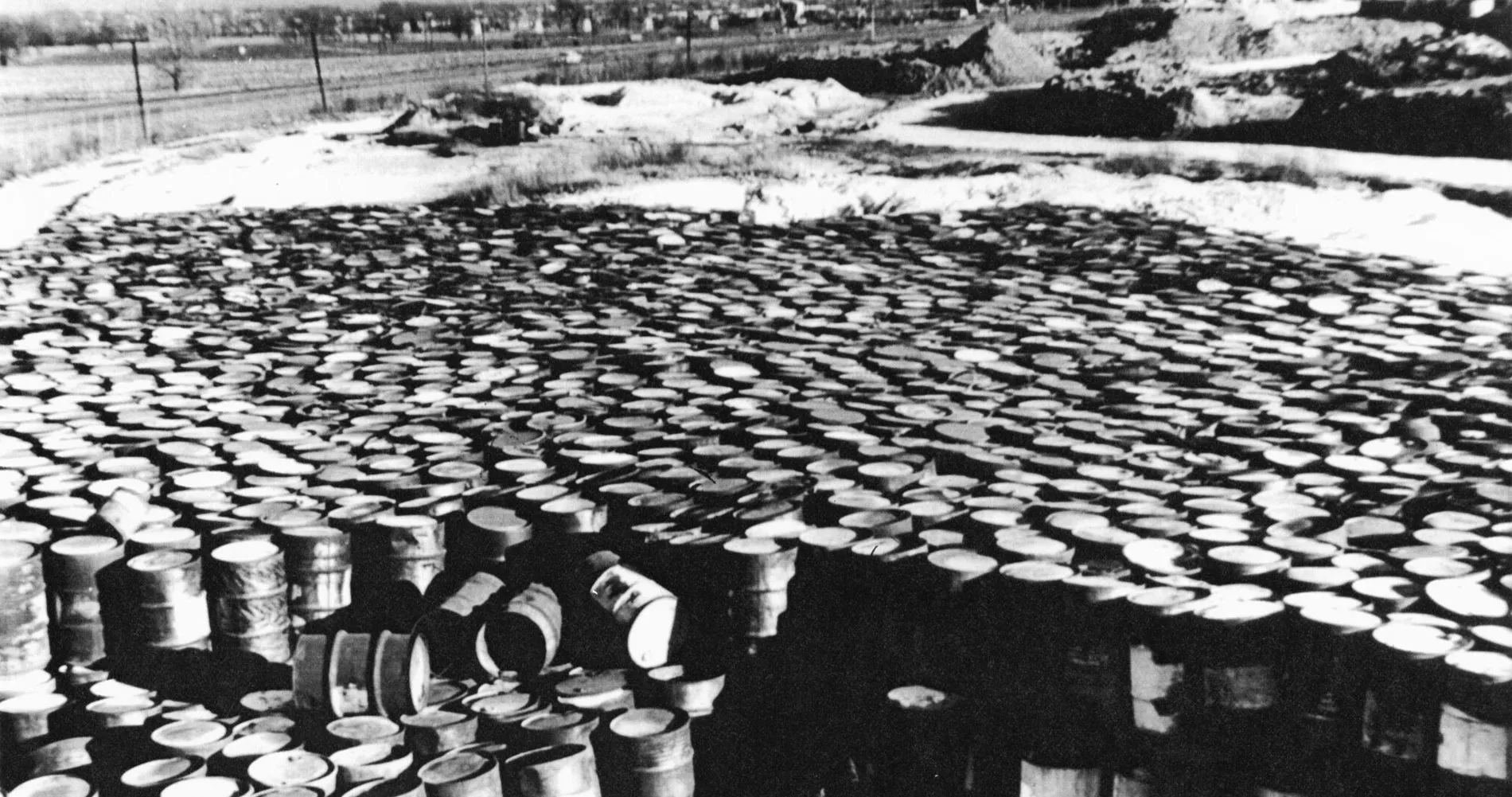

The asymmetry becomes more pronounced when examining reconstruction. According to the World Bank, the EU and the UN, Ukraine’s reconstruction needs are estimated at USD 524 billion (EUR 506 billion) over the coming decade. The EU’s entire debate about frozen Russian assets revolves around the principle that those responsible for destruction should contribute to rebuilding. Gaza’s needs, assessed at USD 53.2 billion in February 2025 and later revised to nearer USD 70 billion as the magnitude of the devastation and rubble removal became clearer, have prompted no serious EU discussion about compelling Israel to finance reconstruction. The principle so forcefully invoked in the case of Ukraine appears conspicuously absent in the case of Gaza.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin in March 2023 related to the unlawful deportation of Ukrainian children. In November 2024, ICC judges similarly issued arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defence Minister Yoav Gallant, alleging war crimes and crimes against humanity, including starvation as a method of warfare. However, the broader international legal assessments diverge sharply. No UN body has declared that Russia is committing genocide in Ukraine, whereas in September 2025 the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry determined that Israel’s actions in Gaza amount to genocide, a finding Israel rejects, yet it underscores the gravity of the accusations. In spite of these differing assessments, the EU treats Russia as a serious offender, relying on ICC findings to justify unprecedented sanctions, while effectively disregarding the far more serious assessment of Israel’s actions by the United Nations.

Debates over Israeli actions regularly generate accusations of antisemitism which, while essential to address when legitimate, can also be weaponised to delegitimise or silence critical questioning. In such a context, editors and media organisations often favor caution, narrowing the range of permissible inquiry. Nunziati’s question, which highlighted an inconsistency in the EU’s application of its own established logic, became reframed as biased or inappropriate, enabling disciplinary action and fuelling online backlash.

His experience is not merely an isolated episode of editorial overreach but reveals the pressures shaping European media environments. It illustrates how geopolitical sensitivities, institutional risk management, and uneven applications of accountability converge to constrain journalistic autonomy. When a straightforward question at a public briefing becomes grounds for termination, the issue is no longer just one of double standards in foreign policy but of the health of democratic debate within the EU itself.

The EU frequently asserts that accountability for civilian suffering is a universal principle. Yet universality collapses when principles are inconsistently applied. If the Union aspires to uphold a rules-based international order, consistency is not a rhetorical luxury but a moral and legal obligation. The credibility it seeks to project globally, will increasingly depend on whether it is perceived as shielding certain allies (Israel) from scrutiny while demanding full accountability from others, which it classifies as it enemy (Russia).

In this sense, the real question raised by the Nunziati Affair is no longer simply whether Israel should be held to the same standard as Russia. It is whether Europe is willing to hold itself to the standards it professes.