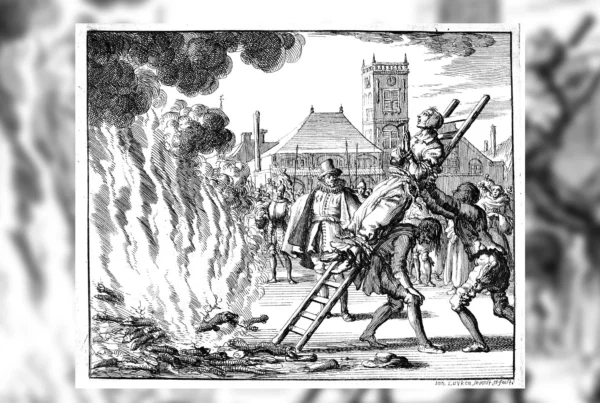

The Gulabi Gang is helping Dalit women stand up for their rights and fight for justice and equal treatment under the law. Armed with bamboo sticks and dressed in pink sarees, they have taken justice into their own hands. The gang’s existence is an indictment of India’s failure to protect vulnerable women. Despite constitutional prohibitions, caste-based discrimination persists due to deep-seated religious and social structures. Dalit women account for 90% of rape victims in India.

Michael Thake

10 March 2025

Arabic version| French version | German version

Every year on March 8, millions observe International Women’s Day (IWD), celebrating the social, economic, cultural and political achievements of women while reaffirming the urgent need to combat gender bias, stereotypes, and discrimination. This year’s theme, “Accelerate Action” for 2025, underscores growing frustration over stalled progress on gender equality, emphasizing a shift from mere awareness to tangible action.

In recent times, solidarity movements such #Metoo, #TimesUp, #BalanceTonPorc and #NiUnaMenos, saw an unprecedented number of women speaking up against sexual harassment and violence, leading to public and judicial action against structural inequalities and the perpetrators themselves, mostly exercised within the confines of state authority and lawful interventions.

The Gulabi Gang, armed with bamboo sticks (lathis) and clad in their signature pink sarees, gained substantial international recognition by literally taking justice into their own hands – inviting both acclaim and notoriety within India.

Founded in 2006 by Sampat Pal Devi in Uttar Pradesh’s Bundelkhand region in India, the Gulabi Gang emerged as a response to the widespread and systemic gender violence and government inaction faced, to an inordinate degree, by Dalit women. According to Times of India, nearly 400 000 women between the ages of 18 and 60 are members, drawn to the group’s direct and extrajudicial methods of seeking justice in a system that is notoriously slow and victim-stigmatizing.

The group’s grassroots vigilantism captured national attention and imagination, particularly with the release of the 2014 Bollywood dramatization Gulaab Gang, reflecting India’s growing concern for women’s rights. Yet, as researcher Victoria Bui notes in Aletheia (2025) “feminist movements in India catered to educated, middle-class women, thereby excluding women inhabiting the lower rung of the caste system”. The Gulabi Gang challenges this status quo, offering an alternative for Dalit women often sidelined by mainstream activism.

Members of the gang not only support women by lawful means, such as by creating a school in Banda and helping illiterate women apply for government assistance, but also through vigilante actions that include the public shaming of abusers, confrontation of corrupt officials and employing gherao (encirclement protests). Writing for the journal Feminism and Psychology (2009), White & Rastogi recount the instance where local government officials disconnected Banda families from electricity for two weeks to extort money and sexual favors. The Gulabi Gang encircled the baffled officials and successfully coerced them to rethink their short-sighted racket.

Vigilantism is a contentious issue, often seen as both a symptom of weak state institutions and a necessary form of grassroots justice. At its core, vigilantism can challenge the state’s monopoly on justice, risk undermining democratic institutions and escalating tensions with authorities, rather than allow collaborative and sustainable approaches to flourish. However, Bui stresses that timely relief is crucial for women facing abuse, noting that the Gulabi Gang, “unencumbered by bureaucratic delays… can directly intervene in ongoing offenses where local authorities consistently fail to act.”

The gang’s existence is as much an indictment of India’s failure to protect vulnerable women as it is a testament to the resilience of grassroots activism. Despite constitutional prohibitions, caste-based discrimination persists due to deep-seated religious and social structures. National Geographic’s Mayell highlights how Dalits remain systemically excluded, despite legal frameworks like the 2006 Prohibition of Child Marriage Act and India’s ratification of CEDAW. Domestic violence, child marriages, and dowry-related abuses remain rampant, disproportionately affecting Dalit women.

The UN Development Programme (2021) reports that Dalit families are overrepresented in communities of multidimensional poverty, suffer higher illiteracy rates, and account for 90% of rape victims in India. This intersection of economic, social, and gender-based exclusion, combined with government inaction, creates a system of impunity where legal recourse is scarce.

Documentary filmmaker Nishtha Jain, in a 2017 Q&A about her film on the Gulabi Gang, underscores the significance of the movement beyond activism, where for many of these women “there is no individual agency, throughout their lives they spend according to their parents, their husband’s and then their children’s needs, so even if they joined Gulabi Gang to go for a picnic, they did something for themselves… which is huge.”

The Gulabi Gang exists at the crossroads of tradition and modernization, where legal protections remain unenforced due to entrenched cultural norms. Its inclusive, vigilante foundation enables women-led leadership, rapid intervention, and a built-in support network. While its tactics may be controversial, the group fills a void left by a system that routinely fails its most vulnerable citizens.

For Western onlookers, the Gulabi Gang serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of weak democratic, judicial, and policing institutions. With Freedom House (2024) reporting an 18th consecutive year of global democratic decline, the case of the Gulabi Gang underscores the importance of safeguarding minority and women’s rights through strong institutions. As the Women, Peace and Security Index (2023/2024) argues, nations with free and fair elections, robust civil society autonomy, and accountable governments tend to be those where women thrive. The lesson is clear: when legal systems fail to protect the vulnerable, alternative forms of justice will inevitably emerge.

Picture: INDIA UP Bundelkhand, women movement Gulabi Gang in pink sari fight for women rights and against violence of men, corruption and police arbitrariness, protest rally in Mahoba Mahoba Uttar Pradesh India. © IMAGO / Joerg Boethling

Other Articles Which Might Interest You

India’s Castocracy: Dalit Outcasts in the Caste System