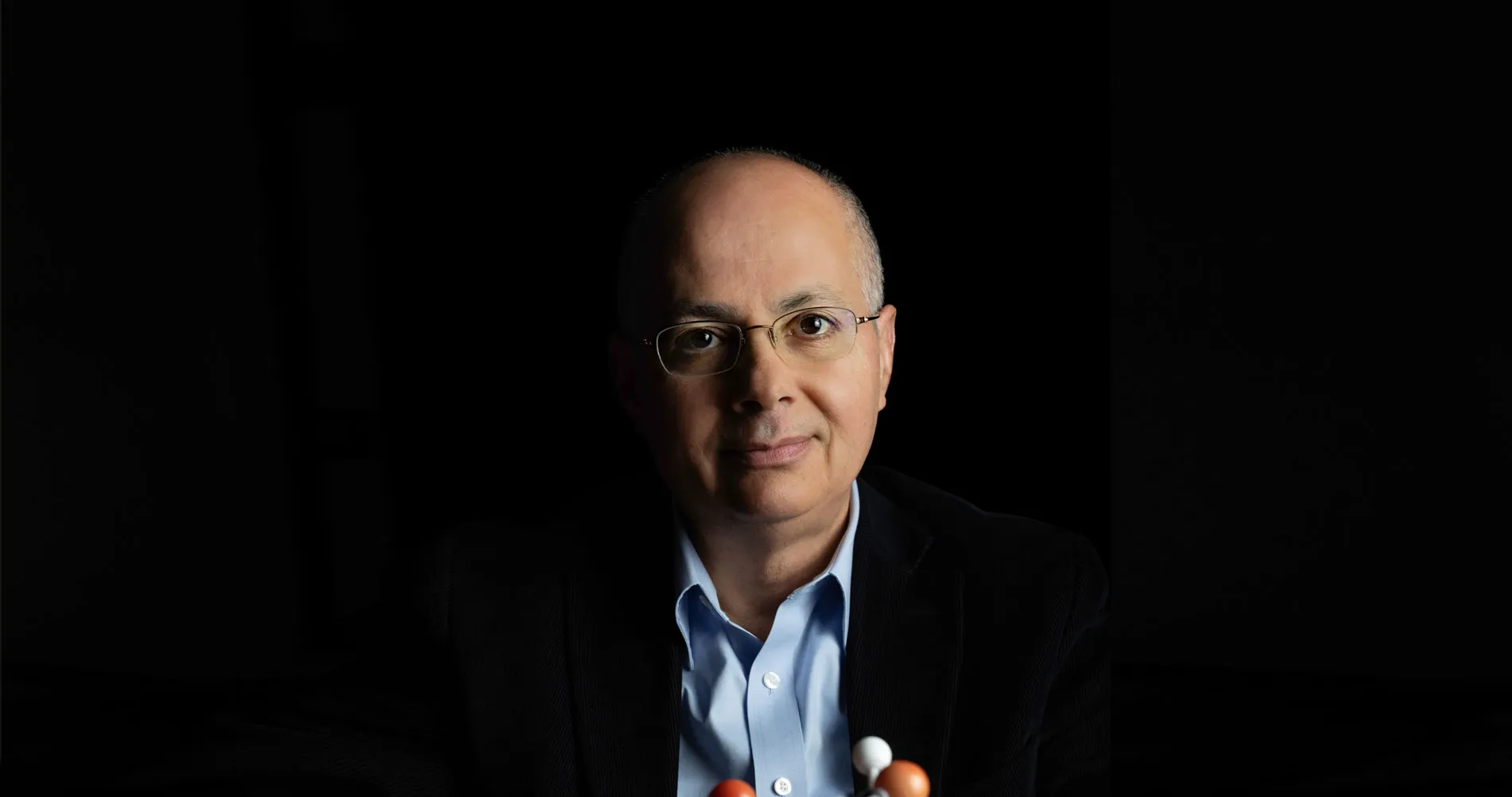

The US is negotiating a rare earth deal with the DRC. Since the trade war with China has restricted US access to China’s rare earth supply, the US is exploring alternative sources for these vital minerals. The Ukraine rare earth deal has so far not materialized and President Trump has now tasked his Senior Africa Advisor, Massad Boulos, to close the deal with DRC.

Michael Thake

30 April 2025

Chinese version | French version | German version

The conflict in the mineral-rich Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has accelerated since January 2025. The Rwandan-backed rebel group M23 captured the cities of Goma and Bukavu in a rapid offensive, leaving at least 7000 civilians dead and displacing thousands. The DRC government’s control over key mining provinces is threatened.

President Donald Trump’s Senior Adviser for Africa, Massad Boulos, recent statement regarding a minerals deal was optimistic: “You have heard about a minerals agreement. We have reviewed the Congo’s proposal. I am happy to announce that the president and I have agreed on a path forward for its development.” Under such an agreement, US defense and tech companies would gain access to Congolese cobalt, lithium, and copper reserves. In return, the US would offer military training and equipment—possibly even troops—to help retake rebel-held zones.

The US depends heavily on China for resources that underpin its economic and national security. The current trade war with China has accentuated this problem. A deal with the DRC could tip the balance—if implemented wisely. Strategically, a DRC deal makes sense. The US must reduce its dependency on China for critical minerals or risk falling behind in defense, manufacturing, and clean energy. But the path forward is narrow, and full of risks. To succeed, Washington must make transparency and governance reform central to the deal, coordinate with allies—like the EU, avoid over-militarizing the partnership, which could backfire and support long-term institutional reform, not just short-term resource extraction. Failure to act would solidify China’s near-monopoly and leave the US vulnerable to economic coercion.

The proposed deal has reignited a pressing geopolitical question: Can the US still counter China’s grip over Africa’s critical mineral wealth, or is it already too late? Currently, DRC’s mineral wealth is mainly dominated by Chinese firms.

Both Beijing and Washington are chasing the raw materials essential for the manufacturing of products, ranging from green technologies to weapons manufacturing. The World Bank’s (2020) “Minerals for Climate Action” report estimates that demand for critical minerals like cobalt, lithium, and graphite will grow by 500% between 2018 and 2050.

The US lacks sufficient domestic cobalt resources and opening new mines at home takes years—sometimes decades. China, by contrast, began securing mining rights and investing into infrastructure projects across Africa, via the Belt and Road Initiative, over the last two decades. So far the US has been absent from African mineral diplomacy and China has been allowed to expand its influence on the continent.

China has spent USD 21.7 billion in Africa in 2023, with approximately USD 10 billion directed toward critical minerals alone. The US, by contrast, has invested a mere USD 7.4 billion – only USD 300 million of which was focused on developing the mineral sector. The US Select Committee on China (2024) also found that China supplies over 50% of US demand for 24 critical minerals, and 90% of its rare earth elements.

China’s dominance stems from decades of planning and state-led industrial policy. Beijing controls not only large-scale extraction, but also refining and midstream processing – building a symbiotic if not codependent relationship with the DRC. By contrast, the US has largely relied on private-sector partnerships in its dealings with African countries, usually including a plethora of local private sector actors, considerable red tape and environment, social and governance (ESG) standards, requiring more cumbersome reform than deals presented by China.

The proposed DRC deal could offer America a breakthrough. It would diversify supply chains, reduce reliance on China, and empower US companies in battery, solar, and defense sectors. The DRC might also align with western partners, potentially improving labor and environmental standards, whose constituents, long complained about Chinese treatment and malpractice. But success is far from guaranteed and US control has already suffered setbacks, such as with the acquisition of the largest cobalt mine in the world within the DRC, by the China Molybdenum Compand (CMOC) from the American company Freeport-McMoRan in 2016.

The US involvement in DRC could fuel positive reforms and help fight corruption – which has long plagued Congo’s mining sector. Contract transparency, community benefit-sharing, and environmental safeguards are essential. Also, the fight against child labor has long been an issue in mining projects in DRC.

Trump’s previous term revealed a lack of interest in Africa beyond trade balances and counterterrorism. His second administration appears more focused on “great power competition”, while remaining skeptical of multilateral engagement. Also, with Trump’s recent implementation of tariffs, especially against China, the search for alternative sources for rare earth minerals is a top priority for the US President.

US Senior Advisor for Africa Boulos has affirmed that “The US remains determined to support the ending of the conflict”. The mineral’s deal would “affirm the territorial integrity of the DRC”. Yet, this optimism is not shared by all, who fear that American firms might become targets of extortion, while the US military is dragged into a prolonged civil war. US military involvement—intended to secure supply lines—risks mirroring past foreign entanglements in Iraq and Afghanistan

The clock is ticking. A minerals agreement with the DRC is not a silver bullet—but it may be America’s last, best chance to rewrite the rules of global mineral supply chains.